When the impossible happened around 1 AM on Saturday, when up to 120 mph winds equivalent to a Category 3 hurricane ripped through Bemidji, Minnesota, something else happened too.

People showed up for each other.

This town gets relentlessly beaten up in regional media for poverty, crime, high crime rates plaguing the community, and all the ways late-stage capitalism tears apart working communities. This town that supposedly has nothing left to give had everything to offer when the unthinkable occurred. Despite 90-degree heat, residents emerged with chainsaws, generators, water, and supplies because that's what a community does.

🌪️ When the Sky Fell Down

The derecho that struck Bemidji wasn't just another storm. Emergency Management and the National Weather Service, conducting damage assessment, confirmed that winds over 105 MPH put the storm at the equivalent of a strong category two hurricane. Mayor Jorge Prince called it the most damaging storm ever to hit the city. That assessment isn't hyperbole when you see houses split open by centuries-old oaks, roofs torn off buildings everywhere, vehicles flipped, and thousands of trees down.

The storm carved a path of destruction that spared no Bemidji neighborhood, demolishing the myth that disasters discriminate by zip code or income level. Over 80% of Beltrami County lost power, leaving thousands without electricity, water, or air conditioning during an intense heat wave.

But here's what the headlines miss: Before the National Weather Service could even confirm the storm's classification, before what's left of federal disaster response could even consider mobilizing, before the state's Emergency Operations Center could fully coordinate, Bemidji was already taking care of Bemidji.

💪 Mutual Aid in Motion

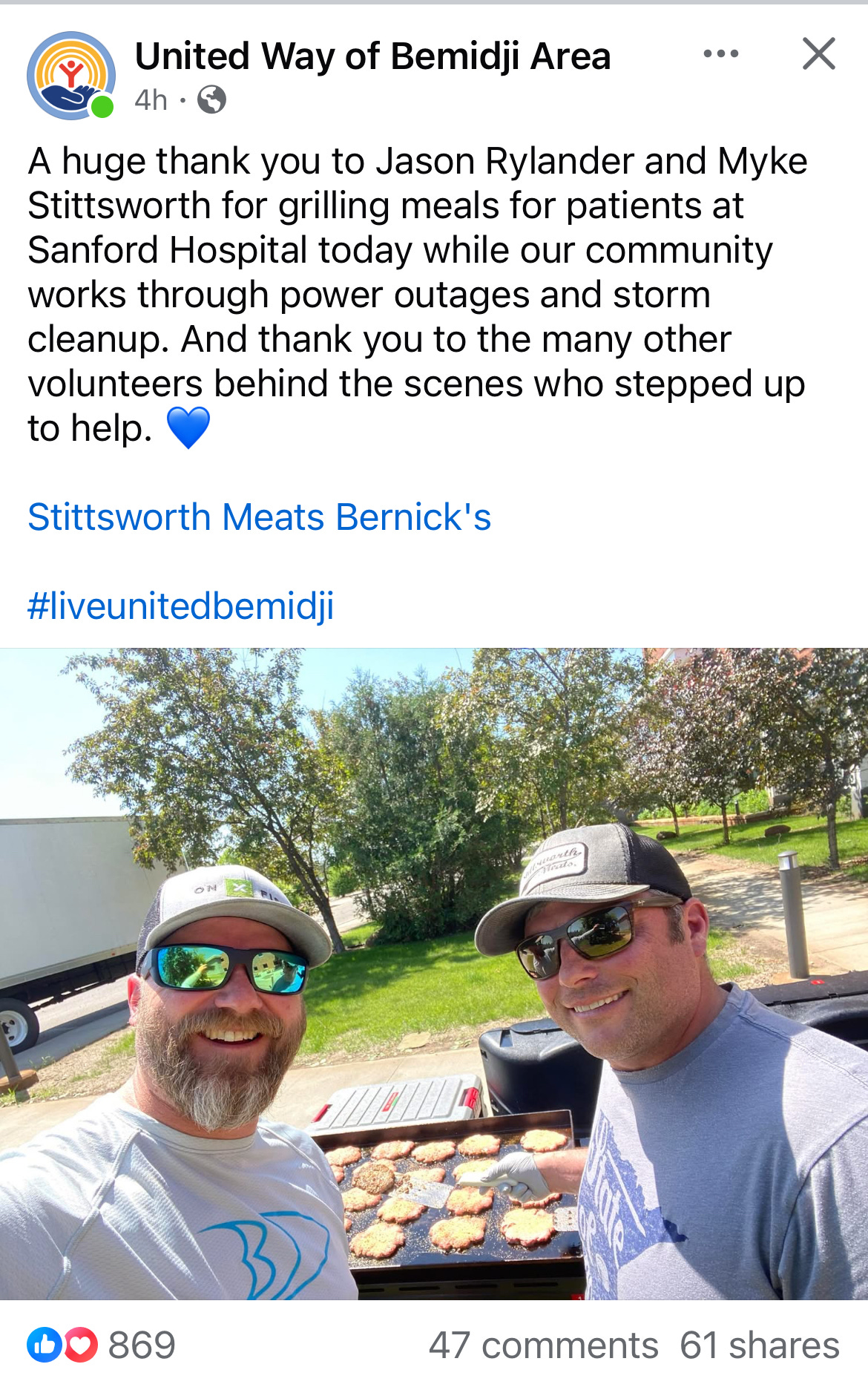

The annual Loop the Lake biking festival around Lake Bemidji was canceled Saturday. Still, food for the event was donated to the Sanford Center, where volunteers cooked burgers and distributed cases of water. Jason Rylander and Myke Stittsworth fired up grills to feed patients at Sanford Hospital. Volunteers unloaded donated water while others wielded chainsaws to clear roads and rescue neighbors.

This wasn't charity—this was mutual aid in its purest form, the kind that Indigenous communities and Black and other marginalized communities have practiced for centuries as a response to and rejection of the injustices they've faced. With a recorded history in Black and Creole communities dating back to the mid-1700s, when official systems fail or move too slowly, communities that understand survival create their own networks of care.

Monaya Magaurn, 40, visited Greenwood Cemetery with an electric chainsaw to clear the graves of her grandparents and father, saying, "I cleaned up my business this morning, so I decided to come down here to try and clean up a little bit." That sentence contains multitudes—the understanding that care extends beyond the living, that recovery is both practical and sacred, and that showing up means doing what needs doing without being asked.

🤝 Networks of Care in Action

What happened in Bemidji reflects a broader pattern emerging across climate-impacted communities. In the face of increasingly severe climate emergencies, mutual aid collectives have emerged as critical actors in providing immediate relief and fostering long-term community resilience. From established local groups distributing food, water, toiletries, and medical supplies immediately after Hurricane Fiona struck Puerto Rico to Imagine Water Works' Mutual Aid Response Network in New Orleans, which facilitated thousands of mutual aid exchanges in response to the pandemic and multiple hurricanes, communities are creating the safety nets that institutions fail to provide.

This isn't new—it's the recovery of something essential. Mutual aid has a recorded history in Black and Creole communities dating back to the mid-1700s and has been widely used within communities of color for centuries. Historically denied equal access to recovery resources such as loans and government aid, members of these communities often depended on one another to get by—pooling money, sharing food, and providing transportation or other needed resources.

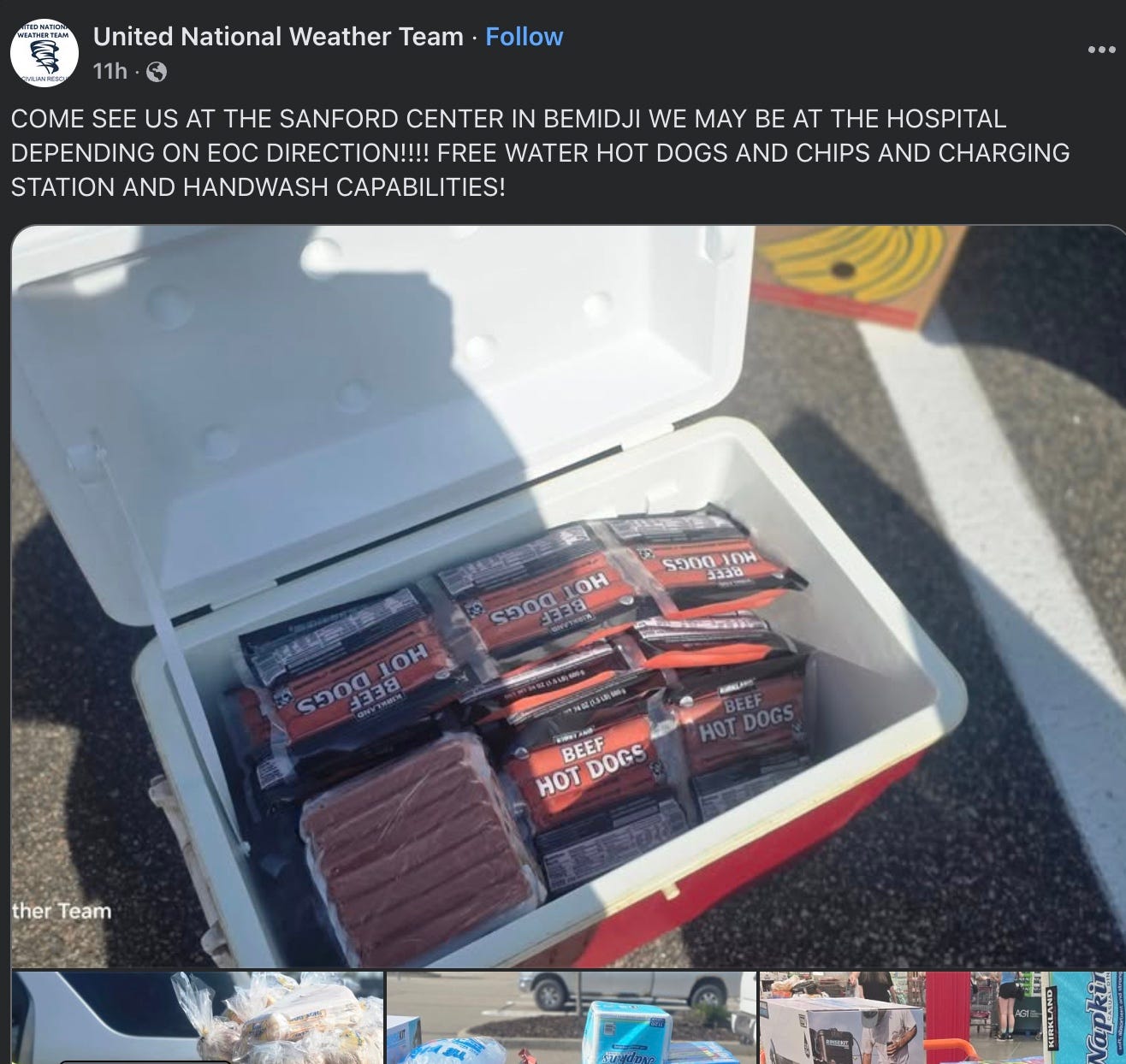

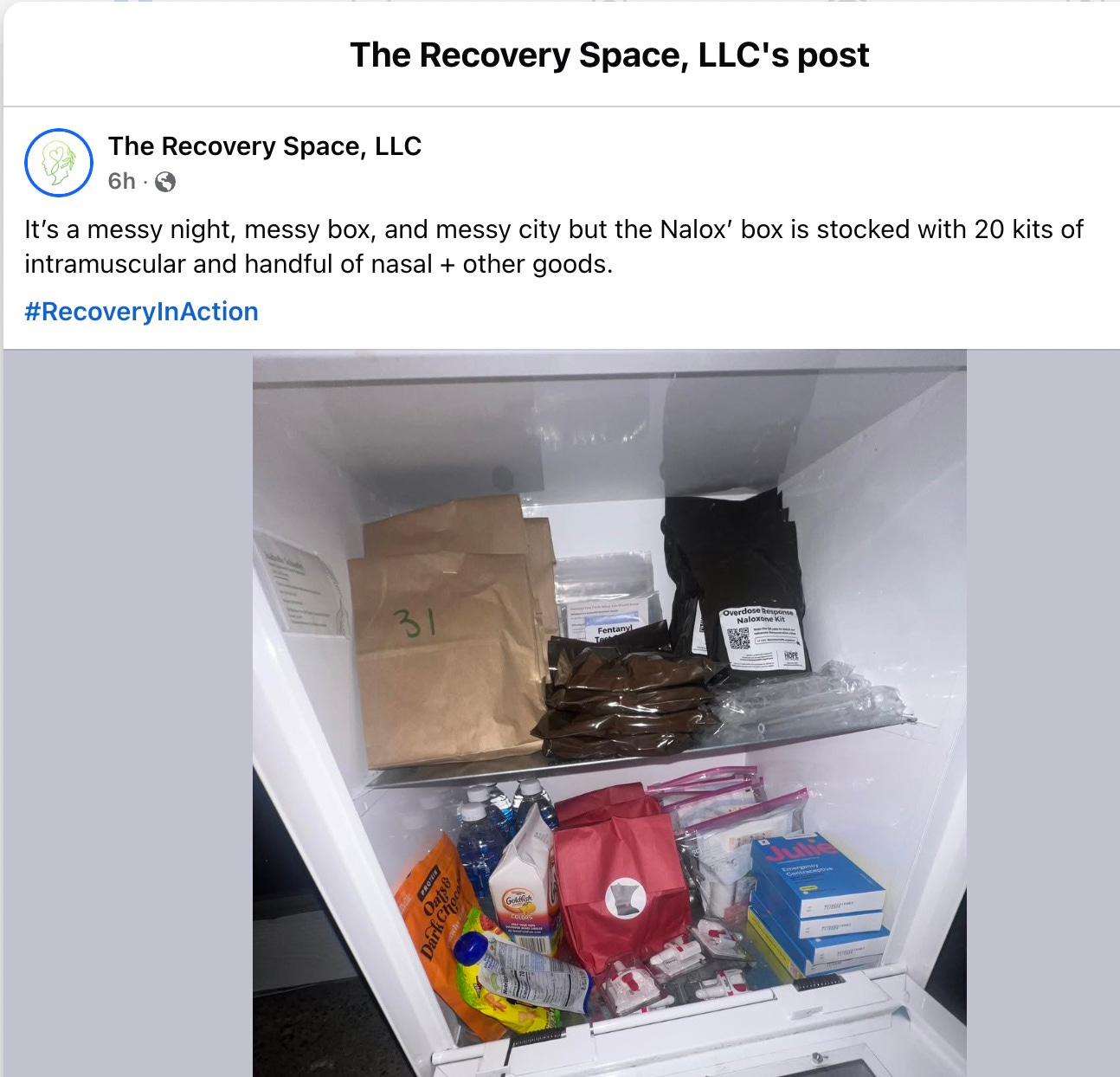

What Bemidji demonstrated isn't extraordinary—it's what communities do when they remember they have each other. The United National Weather Team providing free water, hot dogs, and charging stations. The United Way of Bemidji Area coordinating volunteer efforts. Individual residents checking on neighbors, sharing generators, opening homes to those displaced. As one resident, Charice English, observed: "The only good thing about the storm is that it needs to bring people together".

⚡ Building Power for What's Coming

Governor Tim Walz acknowledged the community response, stating "Our emergency managers are on the ground in Beltrami County and ready to assist local authorities in the wake of severe storms last night. Grateful to hear no reports of anyone losing their life. We'll work together to rebuild". County Board Craig Gaasvig declared that "Tough times like this can shine a light on how much good we have in our community, and how fortunate we are to have people come from other communities and agencies to help us get through this challenging time".

These leaders understand what Bemidji demonstrated: that community strength emerges in crisis. But mutual aid isn't just about responding to disasters—it's about building the relationships and systems that make communities resilient before disaster strikes. By thinking about both the process and product of resilience design, we can help shift resilience design efforts to be more effective for marginalized communities on the front lines of climate change.

The people power that emerged in Bemidji's crisis didn't materialize from nothing. It grew from the soil of existing relationships, from people who already understood that their liberation was bound up with their neighbors'. The question isn't whether Bemidji will face more climate emergencies—increases in precipitation and other extreme weather will continue contributing to flooding, erosion, declining water quality, and negative impacts on transportation, agriculture, human health, and infrastructure. The question is whether communities will be ready with networks of care that don't wait for official permission to start helping.

🌱 What We Can Do Now

The path forward requires both immediate action and long-term relationship building:

Strengthen local mutual aid networks before the next crisis. Connect with existing organizations like the United Way of Bemidji Area and volunteer networks. Create neighborhood contact lists, organize supply shares and skill exchanges, and build the relationships that make rapid response possible.

Press for climate adaptation that centers community needs. Building resilient communities requires expanding green infrastructure and stormwater management, assessing vulnerabilities at critical facilities using climate projections, and combating urban heat islands. Demand that resilience planning include community voices, not just engineering solutions.

Learn from Indigenous knowledge and historical mutual aid practices. For many Indigenous people, collective care is a way of life. We must center traditional ecological knowledge and community-centered approaches to resilience that have sustained communities through generations of challenges.

Challenge disaster capitalism wherever it emerges. Watch for attempts to use crisis as an excuse for privatization, displacement, or policies that benefit the powerful at the community's expense. Learn how to organize community-controlled alternatives to disaster capitalism.

Build political power for systemic change. Individual and community preparedness matter, but local governments must also step up through policy changes that reduce risk and vulnerability in the first place, through more funding for social services or investments in infrastructure projects. Because emergency management policy exists primarily at the local and state levels, communities don't have to wait for federal action.

In the aftermath of Bemidji's impossible storm, residents discovered something always true: They have each other. The trees will regrow, the power lines will be rebuilt, but the networks of care that emerged in this crisis can become the foundation for a different kind of resilience.

My husband John wrote about his own experience helping out yesterday after he assisted friends of mine, some 30 miles from our home, who were trapped by downed trees on their road. He spent hours alongside my friends and their neighbors before I was able to join them, cutting up and removing heavy logs. He shared later:

People from the community helped out however they could. From running chain-saws to offering water, from helping remove branches to pushing obstructions out of the way with their skid-steer. I’m sure all those folks don’t hold the same political beliefs. But that never came up in conversation during our short breaks. We were all just neighbors helping neighbors,and doing what needed to be done. Everyone can now get to town if needed, emergency services can get in if needed. And strangers became friends. If your neighbors are ever in need, please help them if you can. You may be dog-tired at the end of the day, but you’ll have done a ton of good, maybe made some friends, and you’ll appreciate your sore muscles in the morning.

This is what interdependence looks like when the sky falls: People show up with chainsaws, water, grills, and generators, not because anyone told them to, but because that's what communities do.

P.S.

As Bemidji rebuilds, donations are coordinated through the American Red Cross, United Way of Bemidji Area, City of Bemidji, and Beltrami County at the Sanford Convention Center. But the real reconstruction—building systems that can weather any crisis—is work that belongs to all of us, every day, before the next storm arrives.